Am I Masking My Autism? Signs, Effects, and Getting Diagnosed

Imagine spending your entire life performing—carefully observing others, copying their behaviors, suppressing your natural responses, and exhausting yourself trying to fit in. For many autistic people, particularly women and girls, this isn't acting—it's survival. This phenomenon, known as masking or camouflaging, has profound implications for autism diagnosis and represents one of the most significant barriers to understanding the true scope of autism in our communities.

What Is Autistic Masking?

Masking (also called camouflaging or compensating) refers to the strategies autistic people use to hide or suppress their autistic traits in order to appear neurotypical. This might involve practicing social behavior, reducing fidgeting, and correcting posture to fit in better. It's a sometimes conscious and sometimes unconscious effort to navigate a world designed for neurotypical brains.

Masking can include:

Scripting conversations and rehearsing social interactions beforehand

Suppressing stimming behaviors like hand-flapping, rocking, or fidgeting

Forcing eye contact even when it feels uncomfortable or overwhelming

Mimicking others' facial expressions and body language

Pretending to understand social cues you actually find confusing

Hiding intense interests or talking about topics you don't care about

Suppressing sensory reactions to overwhelming environments

The Gender Divide: Why Women and Girls Mask More

The research reveals a striking pattern: camouflage behavior is more common in autistic females rather than males. This gender difference has far-reaching implications for diagnosis and understanding of autism.

Why This Happens

Autistic women and girls and non-binary people may be more likely to mask than autistic men and boys, potentially due to sexism and stereotypes of how certain people 'should' behave. Society places different expectations on girls from an early age:

Social expectations: Girls are often expected to be more socially compliant, quieter, and more focused on relationships

Behavioral standards: Disruptive or "odd" behaviors in girls may be more heavily corrected than in boys

Peer pressure: Girls' social groups often emphasize conformity more intensely

Safety concerns: Women may learn that standing out or appearing different can make them vulnerable

Parent-reported measures reveal that autistic girls use more social masking and imitation strategies than boys, suggesting this pattern begins early in development.

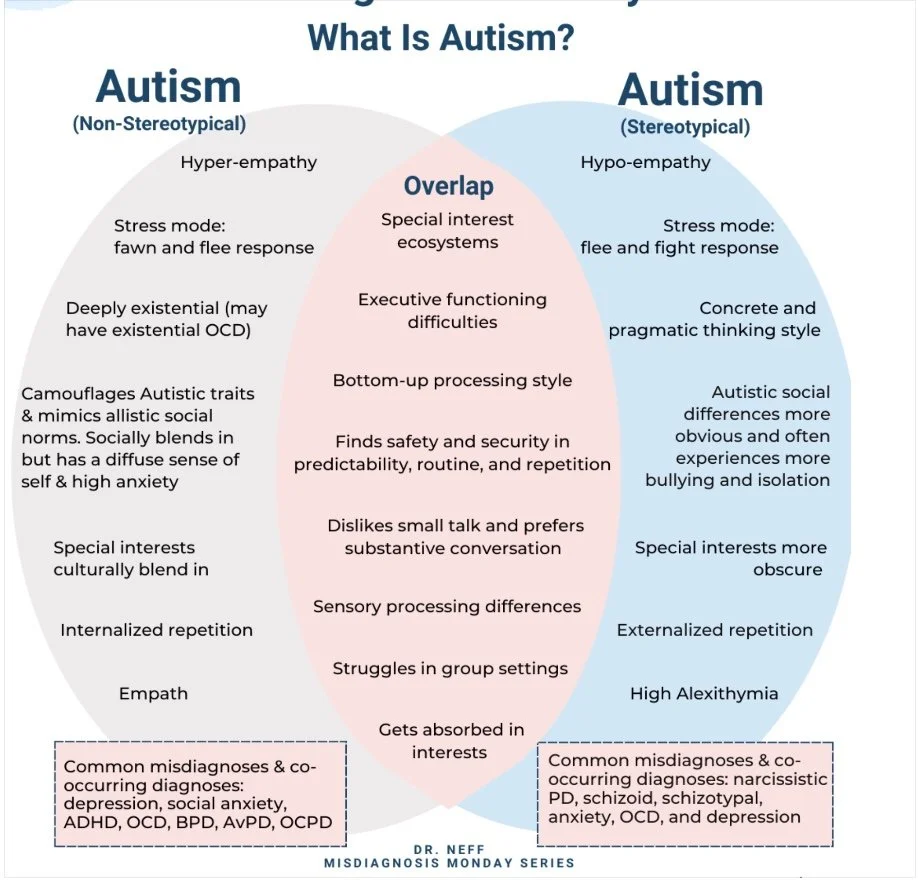

The "Female Autism Phenotype"

Many theories suggest a potential 'female autism phenotype' otherwise known as ‘non-stereotypical autism.’ It can apply to both men and women, although it seems to show up in female populations more. This different presentation often includes:

More internalized behaviors rather than externalized ones

Special interests that appear more "typical" (e.g. horses, celebrities, books, movies)

Better social mimicking abilities

Less obvious repetitive behaviors

Different sensory processing patterns

How Masking Affects Diagnosis

Delayed Recognition

Research shows that unless an autistic female has cognitive or behavioral issues, they are usually diagnosed later. Experts believe family, teachers and primary care physicians may miss the signs because autistic females tend to camouflage their symptoms.

This creates a cascade of missed opportunities:

Childhood: Teachers and parents don't recognize the signs because the child appears to be coping

Adolescence: Social difficulties may be attributed to typical teenage struggles

Adulthood: Years of successful masking make professionals less likely to consider autism

Assessment Challenges

Current autism assessments have significant limitations when it comes to identifying masked autism:

Traditional criteria: Based primarily on studies of autistic boys and men

Observable behaviors: Focus on external presentations rather than internal experiences

Setting bias: Clinical settings may not reveal how someone functions in their daily life

Compensatory skills: High-functioning masking can make autistic traits less apparent

Autism assessments are less sensitive to autistic traits more commonly found in women and girls, creating a systematic barrier to accurate diagnosis.

The Hidden Costs of Masking

While masking might help someone navigate social situations in the short term, it comes with severe consequences that often remain invisible to outside observers.

Mental Health Impact

Masking can lead to worsened mental health, lower self-esteem, autistic burnout, and even suicidal thoughts. The constant effort required to perform neurotypicality is psychologically exhausting.

Common mental health consequences include:

Anxiety disorders: From the constant vigilance required to monitor and adjust behavior

Depression: Often stemming from feeling inauthentic and disconnected from one's true self

Identity confusion: Not knowing where the mask ends and the real person begins

Imposter syndrome: Feeling fraudulent in all aspects of life

Autistic Burnout

Mental and physical exhaustion can lead to autistic burnout, a state of complete depletion that can last months or years. This can lead to what many autistic adults refer to as autistic burnout — a state of intense mental and sometimes physical exhaustion and loss of skills needed to manage daily life.

Burnout symptoms include:

Loss of previously acquired skills (speech, executive function, social abilities)

Extreme sensory sensitivity

Inability to tolerate social situations

Physical and emotional exhaustion

Depression and anxiety

People described a collection of life stressors. Masking their autistic traits was often mentioned as a significant factor contributing to burnout.

Physical Consequences

The toll isn't just psychological. Masking can lead to significant psychological (stress, anxiety, identity crisis), social (isolation, exploitation), and physical (burnout, exhaustion) consequences.

Physical symptoms can include:

Chronic fatigue

Headaches and muscle tension

Digestive issues

Sleep disturbances

Compromised immune system

The Diagnostic Journey: Before and After

Pre-Diagnosis: The Struggle for Recognition

Many masked autistic individuals face years of:

Misdiagnosis: Being diagnosed with anxiety, depression, ADHD, or personality disorders instead of autism

Gaslighting: Being told their struggles aren't real because they "seem fine"

Self-doubt: Questioning their own experiences and perceptions

Inadequate support: Not receiving the right kind of help because the root cause isn't identified

Post-Diagnosis: Relief and Challenges

When diagnosis finally comes, it often brings:

Validation: Finally having an explanation for lifelong struggles

Grief: Mourning for the authentic self that was hidden for so long

Identity reconstruction: Learning who you are without the mask

Relationship challenges: Explaining changes to family and friends who "never saw signs"

Breaking the Cycle: Supporting Masked Autistic Individuals

For Healthcare Professionals

Expand diagnostic criteria: Consider internal experiences, not just observable behaviors

Ask direct questions: About sensory experiences, social exhaustion, and masking strategies

Consider gender differences: Understand that autism can present differently in women and girls

Look beyond the surface: A person who appears to be coping may be struggling intensely

For Families and Friends

Believe their experiences: Don't dismiss someone's struggles because they "seem fine"

Learn about masking: Understand that appearing neurotypical takes enormous effort

Support authenticity: Create safe spaces where they don't need to perform

Recognize burnout signs: Watch for exhaustion, withdrawal, or loss of skills

For Individuals Who May Be Masking

Trust your experiences: Your internal reality is valid, even if others can't see it

Seek appropriate assessment: Find professionals who understand masking and female presentations

Practice unmasking gradually: Start in safe environments with trusted people

Prioritize self-care: Recognize that masking is exhausting and you need recovery time

Creating a More Inclusive Future

Changing Diagnostic Practices

The medical community needs to:

Update assessment tools to capture masked presentations

Update assessment tools to include the non-stereotypical presentation of autism

Train professionals to recognize subtle signs of autism

Develop gender-sensitive diagnostic criteria

Consider self-reported experiences alongside observed behaviors

Building Accepting Communities

Society as a whole can help by:

Normalizing neurodivergence: Making autism acceptance mainstream

Questioning stereotypes: Moving beyond narrow ideas of what autism "looks like"

Supporting self-advocacy: Listening to autistic voices about their experiences

Creating inclusive spaces: Where people don't need to mask to belong

The Path Forward

Understanding masking is crucial not just for improving diagnostic practices, but for recognizing the full scope of human neurodiversity. Improving our understanding of camouflaging, along with other possible 'female-phenotypes of autism', may further facilitate the identification of masked symptoms and difficulties and enhance timely diagnosis and support.

Every person who has spent years masking their true self deserves recognition, support, and the opportunity to live authentically. By expanding our understanding of how autism presents across all genders and backgrounds, we can build a world where masking becomes a choice rather than a survival strategy.

The conversation about masking challenges us to look deeper, listen more carefully, and recognize that autism—like all human experiences—comes in countless forms. When we understand masking, we understand that many people who appear to be thriving are actually struggling in silence, and that recognition itself can be the first step toward healing and authentic living.

Resources and Additional Learning

Additional neurodiverse resources and recommendations - people to follow and learn from, and places to find additional diagnosis support

Autism Self Advocacy Network - Self-advocacy resources and community support

The Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network - Specific resources for women and non-binary autistic individuals

Autism Research Centre, University of Cambridge - Latest research on autism and masking

Reframing Autism - Australian organization focused on strengths-based approaches

Autistic burnout expertise with Dr. Alice Nicholls - UK psychologist specializing in autistic burnout

Neurodivergent Insights - differentiating between stereotypical and non-stereotypical autism

If you recognize yourself in this description of masking, know that you're not alone. Your experiences are valid, and seeking support—whether through formal diagnosis or community connection—can be a powerful step toward living more authentically.

Hi, I’m Catherine. I’m so happy to share this time and space with you.

I’m a counselor and self-trust coach living on the Emerald Coast of Florida, on the unceded land of the Muscogee. I am a creative, mystic, and neurodiverse adventurer. I love writing, creating, and connecting.

I love helping folx Befriend Your Inner Critic and Become Your Own Best Friend. I enjoy hearing from you and walking alongside you on your journey.

With a full heart,

Catherine

Research Citations and Sources

This article draws from current research on autism masking and camouflaging:

Key Research Studies:

Hull, L., et al. (2020). "Gender differences in self-reported camouflaging in autistic and non-autistic adults." Autism, 24(2), 352-363. DOI: 10.1177/1362361319864804

Cage, E., & Troxell-Whitman, Z. (2019). "Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults." Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 1899-1911. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x

Mandy, W. (2019). "Social camouflaging in autism: Is it time to lose the mask?" Autism, 23(8), 1879-1881. DOI: 10.1177/1362361319878559

Young, H., et al. (2018). "Development of a conceptual framework of autistic masking." Autism Research, 11(12), 1613-1626. DOI: 10.1002/aur.2036

Additional Research:

Rynkiewicz, A., et al. (2019). "An investigation of the 'female camouflaging phenotype' in autism." Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(6), 2427-2442. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-019-04016-3

Tubío-Fungueiriño, M., et al. (2021). "Social camouflaging in females with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review." Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(7), 2190-2199. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-020-04695-x

Miller, D., et al. (2021). "The development of camouflaging behaviours in autistic girls and boys." Autism Research, 14(8), 1675-1688. DOI: 10.1002/aur.2526

Clinical and Review Papers:

Hull, L., et al. (2017). "Putting on my best normal': Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions." Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2519-2534. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5

Lai, M. C., et al. (2015). "Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism." Autism, 21(6), 690-702. DOI: 10.1177/1362361316671012

Professional Resources:

ADOS-2 and ADI-R Updates for Female Presentations - Updated assessment tools

National Autistic Society Professional Resources - Training and guidance for healthcare providers